|

How does teaching experience affect attitudes towards literacy learning in the early years?

Noella M. Mackenzie, Brian Hemmings and Russell Kay

Charles Sturt University

Teachers bring a complex array of beliefs and attitudes to the teaching of literacy. The purpose of the study reported in this article was to investigate the nature of teacher attitudes towards the learning and teaching of writing in the first year of school and to identify any broad underlying attitudinal dimensions. The secondary aim was to examine the influence of experience on these attitudinal dimensions. Government school teachers (n=228), from two Australian states, were surveyed using an instrument consisting of attitude statements which related to the learning and teaching of early literacy and more specifically early writing. An exploratory factor analysis was undertaken which indicated that, although most items appeared to be unrelated, a set of eight items coalesced to form a scale referred to as Teacher Attitudes towards Language, Thinking and Scaffolding. Analyses of variance were conducted to examine the relationship between teaching experience in general as well as specific early years teaching experience with the teacher attitude measure as the dependent variable. General teaching experience was not found to be significantly related to teacher attitude but increased amounts of early years teaching experience were found to significantly relate to support for a Vygotskian approach to the learning and teaching of writing in the first year of school. The outcomes identify the potential impact of accrued early years experience on teacher attitudes towards the learning and teaching of literacy to young children. While many of the teacher attitudes appeared to be disparate, the identified dimension indicates that there may be a consistent pattern of attitudes related to a Vygotskian approach to learning and teaching early writing. A second implication may be that longer periods of early years teaching experience may foster positive attitudes towards a Vygotskian teaching approach more quickly than general teaching experience in other settings.

The data discussed in this article originate from a program of research which examines the learning and teaching of writing in the first year of school. This research program addresses a number of questions, although the discussion here is limited to the attitudes of Kindergarten/Preparatory teachers towards the learning and teaching of early writing and the link between such attitudes and accrued teaching experience. Attitudes were defined as "evaluated beliefs which predispose the individual to respond a preferential way" (Burns, 1997, p. 456). The attitudes were identified through a survey conducted in late 2008.

It has been argued that "beliefs elicited through questionnaires may reflect teachers' theoretical or idealistic beliefs - beliefs about what should be", while "actual classroom practice may be more rooted in reality...and reflect teachers' practical or experiential knowledge" (Phipps & Borg, 2009, p. 382). However, this does not appear to be a serious problem as previous studies using survey methods to examine teachers' literacy practices are substantiated by findings from observational research (Gambrell, Morrow, & Pressley, 2007).

The survey used in the present study provided an opportunity for Kindergarten/Preparatory teachers to respond to statements about the learning and teaching of literacy, and specifically early writing, from a variety of perspectives. Some teachers believe that literacy learning is skills-based and subsequently they teach literacy using traditional teacher-directed, didactic approaches (Stipek, 2004). Other teachers use a socio-cultural framework to form the basis of their teaching program (McNaughton, 2002). This framework takes account of the many factors that shape classroom learning. Of course, many teachers apply elements of both approaches. The attitudinal statements appearing in the survey reflected differing perspectives and were gleaned from a variety of sources, trialled with a small group of teachers, refined, and then used in a study with 89 teachers in 2007. The survey was subsequently revised before its use in the study discussed here.

Teaching literacy is particularly challenging at a time when a range of views flourish on how to promote literacy learning and teaching (Taylor, 2007). Shifting understandings of literacy and multi-literacies make it increasingly difficult for teachers to know how to approach the teaching of literacy (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000; McDougall, 2010). An institutional and political push for formal literacy instruction and testing in the United States of America, the United Kingdom, and Australia (Genishi & Dyson, 2009) has impacted on literacy instruction in classrooms with a press for more formalised approaches to instruction.

In Australian classrooms, literacy instruction is usually divided into a number of strands which come under the banner of the 'literacy block'. The literacy block is often divided into instructional units and usually includes: reading; writing; spelling; handwriting; grammar; listening and speaking; phonics and phonemic awareness; and may include viewing and representing. This approach seems likely to continue as the new Australian Curriculum organises English into three strands: Language, Literature, and Literacy (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority, 2010). The literacy strand includes reading, writing, listening, speaking, vocabulary development, spelling, handwriting, and phonics. Consequently, the learning and teaching of writing is seen as one part of literacy learning and as such may be taught in isolation.

Teaching which reflects Vygotsky's theories of learning involves organising teaching and learning experiences in ways that are often prevalent in early years classrooms. That is, instruction is planned to give practice within the zone of proximal development for individual children, cooperative learning activities are designed with groups of children operating at different cognitive levels, and scaffolding is a commonly-used strategy to assist and promote individual growth (Bodrova & Leong, 2007; Talay-Ongan, 2004; Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976)

During the 1970s and 1980s it was suggested that there was a relationship between teachers' effectiveness and years of experience (Murnane & Phillips, 1981; Klitgaard & Hall, 1974), although not necessarily significant or linear. While some studies (see for example, Nye, Konstantopoulos, & Hedges, 2004) established that inexperienced teachers (i.e., those with less than 3 years of experience) were typically less effective than more senior teachers, Darling-Hammond (2000b) argued that the benefits of experience appeared to level off after 5-8 years. More recent studies suggest that experience may assist with effectiveness, although some experienced teachers actually become less effective later in their careers (Chingosa & Peterson, 2010). Hattie (2009) differentiates between experienced and expert teachers, suggesting that experience alone is not enough to determine effectiveness. In a study conducted by Hindman and Wasik (2008), the more experienced teachers expressed greater levels of agreement with research-based findings about learning and teaching oral language.

The majority of the other items in the survey appeared to be quite discrete and did not contribute to any coherent factor structure. Some examples of these items are listed in the Appendix.

| Item |

| Language enables thought, making children's talk an essential part of the writing classroom. |

| Language development is facilitated by interaction between inexperienced (children) and experienced (teachers and adults) language learners. |

| Learning to write is enhanced if children are encouraged to build on their home and community experiences. |

| Children use drawing to communicate and as a scaffold, rehearsal, or elaboration technique in their writing. |

| Children learn best when their learning is scaffolded by a more experienced other who can teach to the point of need. |

| Kindergarten children should be encouraged to think 'out loud' (e.g., talk as they write). |

| Expressing their own ideas is the major purpose for writing in Kindergarten. |

| Drawing may act as a bridge between a child's home/community experiences and school by providing opportunities for meaningful conversations. |

| Teaching experience (years) | Mean | Standard deviation | N |

| 0-4 | -.097 | .593 | 48 |

| 5-10 | -.028 | .524 | 38 |

| 11-20 | -.029 | .561 | 40 |

| 21+ | .121 | .566 | 55 |

| Total | -.002 | .566 | 181 |

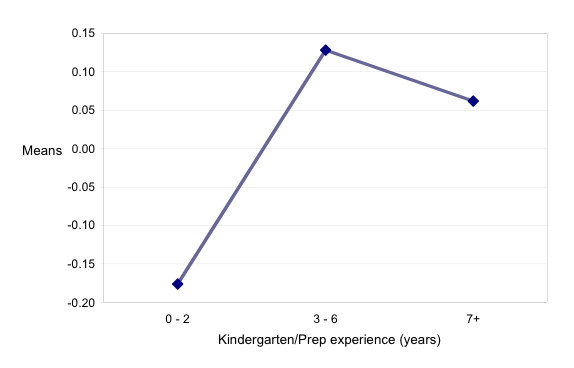

A further one-way ANOVA was carried out to investigate the relationship between the attitudinal scale measure and three categories of Kindergarten/Preparatory teaching experience in years, viz., 0-2, 3-6, and 7+. The descriptive statistics for these categories are given in Table 3. It needs to be noted that the 0-2 category is made up of about 66% of teachers with less than four years of general teaching experience, the 3-6 category has approximately 53% of teachers with 11 or more years of general teaching experience, and the 7+ category has 70% of teachers with more than 21 years of general teaching experience.

| K/P teaching experience (years) | Mean | Standard deviation | N |

| 0-2 | -.176 | .559 | 65 |

| 3-6 | .128 | .490 | 60 |

| 7+ | .062 | .607 | 56 |

| Total | -.002 | .566 | 181 |

The analysis was significant, F(2,178) = 5.26, p=.006 and the adjusted R2 (or effect size) was .045. Group comparisons were undertaken using the Tukey HSD which showed that there was a significant difference between the 0-2 group and the 3-6 group (p=.007). And, that there was also a significant difference between the least experienced group (0-2 years) and the most experienced group (7+ years) at the 5% level. Figure 1 displays a graph for the means of these groups. Taken together, these results indicate that Kindergarten/Preparatory teaching experience has an effect on teacher attitude with respect to language, thinking, and scaffolding. In particular, those teachers with little experience in Kindergarten/Preparatory settings are less likely to hold positive attitudes towards language, thinking, and scaffolding compared to their more experienced counterparts. However, this result may be partly due to the interaction between overall lack of teaching experience and lack of specific K-2 experience.

Figure 1: Means for the three groups of teachers with Kindergarten/Prep experience

A subsidiary aim of the research was to examine the influence of teaching experience on any attitudinal dimensions found. Through the use of ANOVAs it was shown that no significant relationship between years of teaching experience and the identified dimension was evident; however, a significant relationship between years of Kindergarten/Preparatory teaching experience and the attitudinal dimension was recorded. That is, those teachers with limited experience teaching in Kindergarten/Preparatory classrooms were less likely to hold positive attitudes towards a Vygotskian approach to the learning and teaching of writing compared to their more experienced colleagues. To sum, it would seem that accrued early years teaching experience may foster positive attitudes towards a Vygotskian approach in a way that general teaching experience in other settings may not. Of course, this may not be a simple cause-and-effect relationship. For example, teachers with more Vygotskian attitudes may seek teaching placement at the K-2 level. However, the emphasis on the need and skills to become a reflective practitioner in teacher preparation programs over the last 25 years (see, for example, Drew & Bingham, 2001; Gibbs, 1988) might support the view that exposure to K-2 classrooms is necessary to help teachers develop individual frameworks that are socio-cultural. Such frameworks align with Vygotskian principles stated earlier in this article. This possibility is worthy of further research.

At least three qualifications must be borne in mind when assessing the results of the study, particularly in relation to the participants. First, the sample was based upon volunteering for participation. Second, with respect to K-2 experience, at the lower end in particular, teachers tended to be inexperienced generally and inexperienced at K-2 teaching. And third, a reasonable proportion of the participants' responses could not be used in the analysis and this poor response could not be investigated.

Despite these limitations, the study's findings point to a number of important considerations for teachers and those preparing teachers for the classroom. To begin with, if teaching drawing on a Vygotskian approach is seen as an ideal, as supported by teachers with significant exposure to K-2 classrooms, then neophyte teachers need to be encouraged through a mentoring program to use such an approach. This mentoring could involve visits to junior classrooms if the beginning teacher is placed full-time on a more senior class. A system of rotating beginning and seasoned teachers more frequently so that experience is gained on classes in the early years is arguably another way of ensuring more positive attitudes towards a Vygotskian approach to learning and teaching writing and any related skills.

Another consideration involves those preparing teachers for entry to their profession. Maybe greater emphasis needs to be given to the teaching of writing, and one way of achieving this is to have teacher trainees spend additional time in Kindergarten/Preparatory classrooms modelling the practices of effective teachers. An alternative way of having teacher trainees exposed to Kindergarten/Preparatory classrooms is to have a mandated professional experience (or practicum) in such a classroom setting.

A final consideration is that teacher appointments target junior classes in the first instance, if feasible, to promote positive attitudes towards a Vygotskian teaching approach. Valuable experiences in these settings allow early career teachers to then move to more senior classes with increased confidence and skill to support especially struggling students with broader literacy concerns.

Further study, beyond the current research, would be necessary to validate and check the reliability of the Teacher Attitudes towards Language, Thinking, and Scaffolding scale across other samples and jurisdictions. Additional refinement of the scale may make it a useful diagnostic instrument for use in teacher in-service training. Another issue for future research deals with the impact of teacher qualifications and whether or not those teachers who have specialised postgraduate or even extensive in-service training have particular attitudes towards the learning and teaching of writing when compared to other groups of teachers.

It is worth exploring the result that many of the survey items appeared to be quite discrete. This was, no doubt, partly due to high levels of consensus on some items, hence lack of variance, but also because many responses seemed to be unrelated. A possible explanation for this latter finding was that many of the teachers sampled had not yet developed a fully-integrated educational philosophy and drew on a selection of unrelated beliefs/attitudes.

The present study has added to a body of literature pertaining to teaching literacy and teaching experience. Even though the study was not aiming to explore the notion of teaching effectiveness, it does offer some useful insights as to how teaching experience impacts on attitudes to professional practice, and how experience in a particular educational context tends to shape the attitudes of teachers. As advanced by Arbeau and Coplan (2007), this formation of attitudes can have both a direct and indirect influence on students' developmental outcomes.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009). Schools, Australia, 2009. http://abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4221.02009?OpenDocument

Australian Council of Deans of Education (2004). New teaching, new learning: A vision for Australian education. Canberra.

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (2010). Australian Curriculum Consultation Portal, Explore K-10, English. http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/

Australian Labor Party (2007). National platform and constitution. Retrieved 24/5/09, from http://www.nit.com.au/downloads/files/Download_161.pdf

Bennett, K.K., Weigel, D.J., & Martin, S.S. (2002). Children's acquisition of early literacy skills: Examining family contributions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 17(3), 295-317.

Bodrova, E., & Leong, D.J. (2007). Tools of the mind: The Vygotskian approach to early childhood education (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Buckingham, J. (2003). Missing links: Class size, discipline, inclusion and teacher quality (Vol. 29). St. Leonards, NSW: Centre for Independent Studies.

Burns, R. (1997). Introduction to research methods (3rd ed.). Melbourne, Vic.: Addison Wesley Longman.

Chingosa, M.M., & Peterson, P.E. (2010). It's easier to pick a good teacher than to train one: Familiar and new results on the correlates of teacher effectiveness. Economics and Education Review, 30(3), 449-465.

Clay, M. M. (1991). Becoming literate: The construction of inner control. Auckland: Heinemann.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds). (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social features. South Yarra, Vic.: MacMillan Publishers.

D'Anguilli, A., Siegel, L.S., & Hertzman, C. (2004). Schooling, socioeconomic context and literacy development. Educational Psychology, 24(6), 867-884.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000a). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8(1), 1-46. from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v8n1/

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000b). How teacher education matters. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 166-173.

Department of Education, Science and Training (2003). Australia's teachers: Australia's future. Advancing innovation, science, technology and mathematics. Main report. Canberra: Australian Government.

Drew, S., & Bingham, R. (2001). Study skills guide (2nd ed.). London: Gower.

Egan, K., & Gajdamascko, N. (2003). Some cognitive tools of literacy. In A.E. Kozulin, B.E. Gindis, V.S.E. Ageyev, & S.M.E. Miller (Eds.), Vygotsky's educational theory in cultural context (pp. 83-98). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001). From preparation to practice: Designing a continuum to strengthen and sustain teaching. Teachers College Record, 103(6), 1013-1055.

Foote, L., Smith, J., & Ellis, F. (2004). The impact of teachers' beliefs on the literacy experiences of young children: A New Zealand perspective. Early Years International Research Journal, 24(2), 135-147.

Gambrell, L.B., Morrow, L.M., & Pressley, M. (Eds.). (2007). Best practices in literacy instruction (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Genishi, C., & Dyson, A.H. (2009). Children, language and literacy: Diverse learners in diverse times. New York: Teachers College Press.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford: Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic.

Hair, J.F., Black,W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., & Tatham, R.L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Hattie, J.A.C. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Hindman, A.H., & Wasik, B.A. (2008). Head start teachers' beliefs about language and literacy instruction. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(3), 479-492.

Ingvarson, L. (2001). Strengthening the profession? A comparison of recent reforms in the UK and the USA. Quality Teaching Series, Australian College of Education, Paper no. 4.

Klitgaard, R.E., & Hall, G.R. (1974). Are there unusually effective schools? Journal of Human Resources, 10(3), 40-106.

McDougall, J. (2010). A crisis of professional identity: How primary teachers are coming to terms with changing views of literacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 679-687. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.003

McLachlan, C., Carvalo, L., de Lautour, N., & Kumar, K. (2006). Literacy in early childhood settings in New Zealand: An examination of teachers' beliefs and practices. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 31(2), 31-46.

McNaughton, S. (2002). Meeting of minds. Wellington: Learning Media Limited.

Murnane, R.J., & Phillips, B.R. (1981). Learning by doing, vintage, and selection: Three pieces of the puzzle relating teaching experience and teaching preformance. Economics of Education Review, 1(4), 453-465.

Nye, B., Konstantopoulos, S., & Hedges, L.V. (2004). How large are teacher effects? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 26(3), 237-257.

Phipps, S., & Borg, S. (2009). Exploring tensions bewteen teachers' grammar teaching beliefs and practices. System, 37(3), 380-390.

Ramsey, G. (2000). Quality matters. Revitalising teaching: Critical times, critical choices. Report of the Review of Teacher Education NSW, Executive Summary. Sydney, NSW: NSW Department of Education andTraining.

Rivalland, C.M.P. (2007). When are beliefs just 'the tip of the iceberg'? Exploring early childhood professionals' beliefs and practices about teaching and learning. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 32(1), 30-37.

Roehler, L.R., & Cantlon, D.J. (1997). Scaffolding: A powerful tool in social constructivist classrooms. In K. Hogan & M. Pressley (Eds.), Scaffolding student learning: Instructional approaches and issues (pp. 6-42). New York: Brookline Books.

Rowe, K. (2003). The importance of teacher quality as a key determinant of students' experiences and outcomes of schooling. Melbourne, Vic.: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Stipek, D. (2004). Teaching practices in kindergarten and first grade: Different strokes for different folks. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 19(4), 548-568.

Sumsion, J. (2003). Rereading metaphors as cultural texts: A case study of early childhood teacher attrition. The Australian Educational Researcher, 30(3), 67-87.

Talay-Ongan, A. (2004). Early development risk and disability: Relational contexts. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Education Australia.

Taylor, C. (2007). Literacies in childhood. In L. Makin, C. J. Diaz & C. McLachlan (Eds.), Literacies in childhood: Changing views, challenging practice (2nd ed.) ( pp. vii-viii). Sydney: MacLennan & Petty, Elsevier.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1987). The collected works of L.S Vygotsky (Volume 1): Problems of general psychology. New York: Plenum.

Wilcox-Herzog, A. (2002). Is there a link between teachers' beliefs and behaviors? Early Education and Development, 13(1), 81-106.

Wing Jan, L. (2009). Write ways: Modelling writing forms (3rd ed.). South Melbourne, Vic.: Oxford.

Wood, D., Bruner, J.C., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 80-100.

| Authors: Dr Noella Mackenzie is a lecturer in literacy studies in the Faculty of Education at Charles Sturt University. Noella's research interests include early writing development, the relationship between drawing and writing, literacy transitions and pedagogies, teachers' data literacy, and issues associated with teacher morale and the status of the teaching profession. Noella has also published in The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, The Australian Educational Researcher, The Australian Journal of Education and The Journal of Reading, Writing and Literacy. Email: nmackenzie@csu.edu.au Dr Brian Hemmings is the Sub-Dean (Graduate Studies), Faculty of Education at Charles Sturt University. Brian's research interests are quite varied (e.g., the productivity of academics, career change outcomes, and factors affecting school achievement) and his work has been published in journals such as the Asia Pacific Journal of Education, Higher Education, Australian Educational Researcher, and the International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education. Email: BHemmings@csu.edu.au Mr Russell Kay is an Adjunct Senior Lecturer in Education at Charles Sturt University. His research interests concentrate on schooling performance and he draws on the use of multivariate statistics. Russell has published widely and his most recent journal publications appear in the International Journal of Educational Management and Education in Rural Australia. Email: rwkay@exemail.com.au Please cite as: Mackenzie, N. M., Hemmings, B. & Kay, R. (2011). How does teaching experience affect attitudes towards literacy learning in the early years?. Issues In Educational Research, 21(3), 281-294. http://www.iier.org.au/iier21/mackenzie.html |